|

In order for cricket protein to realize its potential impact, we need to get a lot more cricket farms up and running. At Tiny Farms, we made it our mission to solve the hardest problems in cricket production with the goal of making it easy and economically viable to grow crickets at a commercial scale. We worked on a two part solution - a high efficiency cricket rearing system and a high throughput, energy efficient method for processing crickets into cricket protein powder.

By sharing key learnings from our own experience on this site, we hope others will be able to benefit from and build upon our efforts. |

A brief history:

Tiny Farms was birthed in 2012 by Jena Brentano, Andrew Brentano, and Daniel Situnayake. We were actively looking to start a project that could make a big positive impact in the world, and the founding team cared deeply about food, global nutrition, societal stability, and ocean health. Sustainable agriculture was a perfect intersection or these areas of concern, and we quickly focused on protein production due to rapidly growing global demand and the huge proportion of global resources dedicated to producing meat.

Our current agricultural system has reached or exceeded the Earth's carrying capacity for sustainable resource consumption, and the growing demand coupled with climate change, fresh water shortages, and widespread degradation of soils has the us poised to face cataclysmic food shortages in the near future. We believe it is urgent to develop and scale new approaches to food production that produce more from our existing resources and close loops in the nutrient cycle to cut waste. Basically we need to get more from less and do so with systems that can sustain themselves through in an unpredictable environment.

While researching alternative protein sources including algae, fungi, plant based proteins, lab grown meat, and aquaculture, we came across an inspiring TED talk by Dr. Marcel Dicke of Waginengen University titled "Why Not Eat Insects?". It sounded like a good idea to us, so we dove into the background research and were quickly sold by the idea. The only hard question was, would we eat them?

To find out, we caught some grasshoppers out in the garden and fried them up. To our surprise and delight, they were delicious, reminiscent of bacon-wrapped shrimp, and just like tiny lobsters they turned from green to red in the pan. We were sold!

Our current agricultural system has reached or exceeded the Earth's carrying capacity for sustainable resource consumption, and the growing demand coupled with climate change, fresh water shortages, and widespread degradation of soils has the us poised to face cataclysmic food shortages in the near future. We believe it is urgent to develop and scale new approaches to food production that produce more from our existing resources and close loops in the nutrient cycle to cut waste. Basically we need to get more from less and do so with systems that can sustain themselves through in an unpredictable environment.

While researching alternative protein sources including algae, fungi, plant based proteins, lab grown meat, and aquaculture, we came across an inspiring TED talk by Dr. Marcel Dicke of Waginengen University titled "Why Not Eat Insects?". It sounded like a good idea to us, so we dove into the background research and were quickly sold by the idea. The only hard question was, would we eat them?

To find out, we caught some grasshoppers out in the garden and fried them up. To our surprise and delight, they were delicious, reminiscent of bacon-wrapped shrimp, and just like tiny lobsters they turned from green to red in the pan. We were sold!

In 2012, the movement to introduce insects into mainstream agriculture and food culture consisted of a few researchers and a handful of passionate advocates writing a few blogs and hosting occasional tasting events. It was a a wide open field to innovate and advocate. There were also a couple of early companies such as Chapul and Don Bugito.

Our broad mission was to facilitate mainstream adoption of insect based foods by Western consumers. To do this, we faced a two-sided problem: (1) how to present insects as a product consumers would be willing to buy and eat? and (2) where would the insects come from?

We initially focused on problem 1, spending hours in the kitchen experimenting with any bugs we could get our hands on, mostly mealworms, crickets, waxworms, and silkworms. Although we created many delicious dishes and potential products, we quickly realized the lack of supply chain to source insects would prevent any products from catching on in the market.

So we shifted focus to problem 2 and started raising insects ourselves to learn about their life cycles, needs and constraints. We raised silkworms, mealworms, multiple species of crickets, and even ivory cockroaches. We talked to insect farmers who supplied fish bait and pet food stores to learn about the process and concluded that existing farming methods were far too inefficient to realize the potential for insects as a protein ingredient. Live insects could be purchased for ~20/lb plus shipping, which equated to >$100/lb dry weight without factoring any costs for drying or other processing. That price needed to come down by at least a factor of 10 to become a viable ingredient even for premium products.

In a stroke of luck, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UNFAO) released a massive report in early 2013 touting the benefits of insects for use as food and animal feed. The report brought together years of research conducted around the globe highlighting traditional practices and detailing the environmental and economic benefit potential of insect farming. There was massive press coverage and a huge surge in public interest. This was a great opportunity for us to kick into gear and start moving the needle.

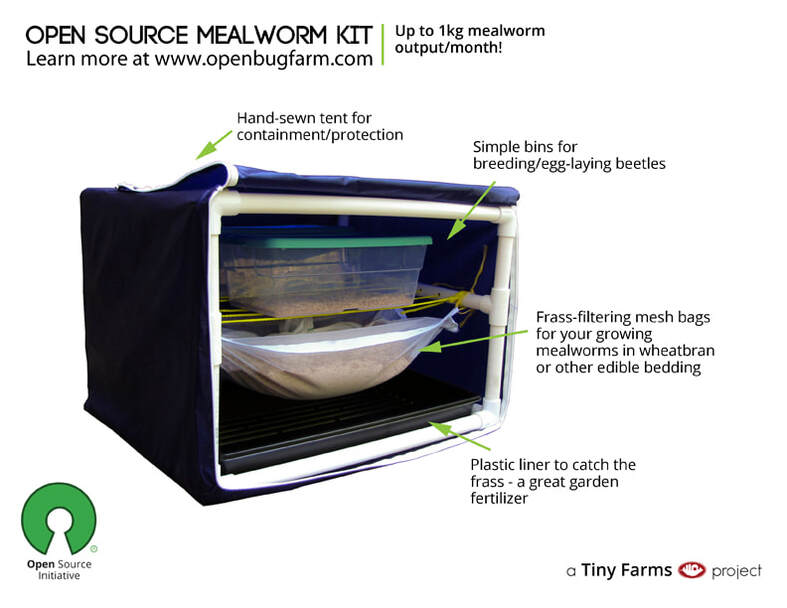

Our early trials showed great promise for raising mealworms based on their lifecycle, habitat, and environmental requirements. In a bid to encourage people to think seriously about insect farming, we designed a simple at-home mealworm farm which we released open source with the launch of our Open Bug Farm project. We also launched a public forum for anyone interested to discuss insect farming. The forum became a huge success and quickly filled with useful information and we sold a number of pre-made mealworm kits. (you can read more about our early days on our blog archive at www.tiny-farms.com/blog)

Our broad mission was to facilitate mainstream adoption of insect based foods by Western consumers. To do this, we faced a two-sided problem: (1) how to present insects as a product consumers would be willing to buy and eat? and (2) where would the insects come from?

We initially focused on problem 1, spending hours in the kitchen experimenting with any bugs we could get our hands on, mostly mealworms, crickets, waxworms, and silkworms. Although we created many delicious dishes and potential products, we quickly realized the lack of supply chain to source insects would prevent any products from catching on in the market.

So we shifted focus to problem 2 and started raising insects ourselves to learn about their life cycles, needs and constraints. We raised silkworms, mealworms, multiple species of crickets, and even ivory cockroaches. We talked to insect farmers who supplied fish bait and pet food stores to learn about the process and concluded that existing farming methods were far too inefficient to realize the potential for insects as a protein ingredient. Live insects could be purchased for ~20/lb plus shipping, which equated to >$100/lb dry weight without factoring any costs for drying or other processing. That price needed to come down by at least a factor of 10 to become a viable ingredient even for premium products.

In a stroke of luck, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UNFAO) released a massive report in early 2013 touting the benefits of insects for use as food and animal feed. The report brought together years of research conducted around the globe highlighting traditional practices and detailing the environmental and economic benefit potential of insect farming. There was massive press coverage and a huge surge in public interest. This was a great opportunity for us to kick into gear and start moving the needle.

Our early trials showed great promise for raising mealworms based on their lifecycle, habitat, and environmental requirements. In a bid to encourage people to think seriously about insect farming, we designed a simple at-home mealworm farm which we released open source with the launch of our Open Bug Farm project. We also launched a public forum for anyone interested to discuss insect farming. The forum became a huge success and quickly filled with useful information and we sold a number of pre-made mealworm kits. (you can read more about our early days on our blog archive at www.tiny-farms.com/blog)

At the same time, a number of startups were launching food products made with cricket powder. Market researh found that consumers were significantly more open to eating products made with crickets compared to other insects. Our conversations with these new companies revealed that our supply crunch predictions were dead on. Even more than convincing people to try their products, these companies struggled to find a reliable and affordable source of food-grade insects to make their products in the first place.

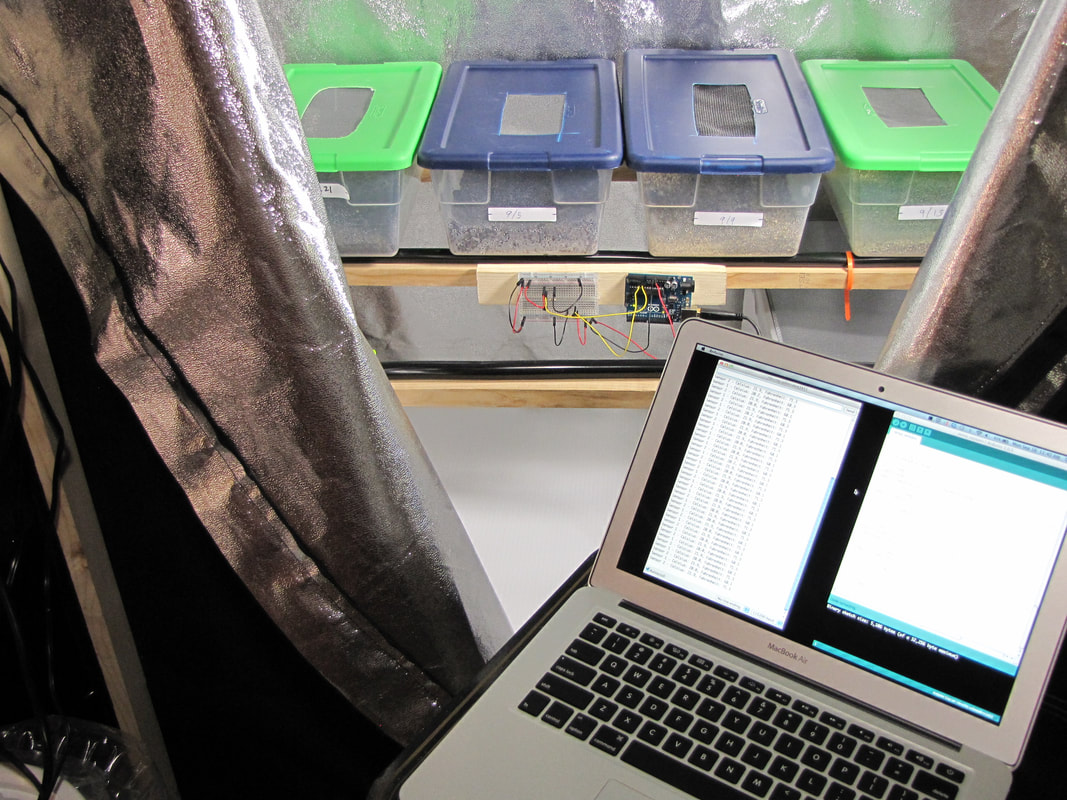

We decided to shift focus from encouraging small scale mealworm farming to figuring out how to grow crickets at a large scale. We built a climate controlled room in our garage and set up our first "bug lab" to get more hands-on experience raising crickets, understanding the shortcomings in traditional methods, and testing new approaches.

We decided to shift focus from encouraging small scale mealworm farming to figuring out how to grow crickets at a large scale. We built a climate controlled room in our garage and set up our first "bug lab" to get more hands-on experience raising crickets, understanding the shortcomings in traditional methods, and testing new approaches.

We built detailed models extrapolating larger scale rearing processes based on our lab work, and isolated the largest cost driver in production as labor associated with setting up habitats, maintaining the populations and harvesting. We prototyped a new approach to housing crickets and providing feed and water that better used the vertical space available, and allowed us to handle and service larger populations of crickets at a time, cutting the labor per cricket raised.

At the start of 2016, we moved into our first commercial warehouse space and built out our first pilot farm, testing and iterating. From that point we were all-hands operating, testing, and improving our farm system. Check out the "Work" page to find details about our R&D and operations.

At the start of 2016, we moved into our first commercial warehouse space and built out our first pilot farm, testing and iterating. From that point we were all-hands operating, testing, and improving our farm system. Check out the "Work" page to find details about our R&D and operations.

When we first launched the farm, we had customers lined up who were interested in purchasing frozen crickets to process themselves. Demand quickly evolved to require ready-to-use cricket powder so we launched another research track to figure out the best way to dry and mill our crickets. Along the way we were awarded SBIR (Small Business Innovation Research) grants from DARPA and USDA which helped fund our ongoing R&D. We also ran a second pilot farm with a partner farmer in Fresno CA.

Starting in 2017 we also saw an exciting market development, with new interest developing in the pet food industry around insect protein. While cricket powder had been competing with other low-cost protein supplements (like whey and soy) in the food market, the pet food market offers an opportunity to utilize cricket protein as a direct replacement for meat in treat and food formulations. Several brands, such as Jiminy's have product in the market, and the big players (Mars, Purina, Smuckers) are watching closely and starting to place bets of their own.

By the time we decided to close shop in 2019, we had demonstrated a new high-throughput energy efficient method for drying crickets co-developed with the USDA ARS, and developed a whole new approach to housing the crickets with a novel substrate that allows for easy large volume mechanized habitat setup and harvest. We are now pleased to share these and other learnings with the world, with the hope that others may benefit from and build upon our work.